In Sweden, in 1939, as Nazi troops began their invasion of Norway, a young American journalist staying in Stockholm began delivering eyewitness accounts of the historic event. She was 28 years old and the only correspondent in that section of the world broadcasting live stories for CBS Radio. Her name was Betty Wason and her vantage point was intimate. Her reports were well-written, authentic, and timely in the transmission of details. She was brave, dedicated, and determined, eventually getting close to Nazi troops in Norway in order to tell the stories of wounded British soldiers and all that they had seen. She was a woman alone in a war zone, a thoughtful writer in a chaotic environment, and a new traveler out discovering foreign lands. But for all the things Betty was, there was one thing she wasn’t. She was not a man.

And that affected everything.

Gender discrimination runs rampant in every field throughout history, except maybe one…. radio news broadcasting in the 1930s and the 1940s. Mainly because there wasn’t any argument against the discrimination. Things were simply done and not done and there were rules to abide by. One of those rules concerned women. Women simply did not, were not, allowed to read the news over the air. It was firmly believed that the feminine register could not convey the seriousness and importance of hard-hitting news stories. Instead, women’s voices were relegated only to entertainment-type shows… cooking lessons, homemaking stories, commercial ads and literature readings. Anything more serious or historically significant was left up to men to communicate on-air. This proved a problem, for our gal Betty.

Growing up in Indiana in the 1920s, Betty was a creative spirit from the start with interests in music, art and fashion design. After graduating from Perdue University with a degree in home economics in the early 1930s, Betty bounced around a few jobs in her home state before realizing she wanted a more exotic life than Indiana could provide. As a young woman full of vivaciousness and adventure and a desire to see the world, Betty went to New York and settled into a two-year job working at McCall’s magazine. But even in the exciting city of New York, her wanderlust could not be quelled. Europe was calling and Betty wanted to travel.

Not having the financial means to live abroad without working, Betty contacted TransRadio Press who was willing to pay young journalists overseas for eyewitness stories concerning World War II. A brief stint in Europe trying to make a go of it as a correspondent didn’t yield enough money for Betty to live on, so she came back to New York only to try again less than a year later. On her second go-around though, she worked with CBS who was desperate to get any and all international news they could get their hands on in regards to the war. That’s when Betty headed to Sweden, just before Hitler arrived in Norway.

There were many male war correspondents living and working overseas at this time, but they were mainly focused on print pieces suitable for newspapers and magazine readers. Radio was becoming more and more popular in terms of delivering news, but the seasoned overseas reporters, so focused on their writing, were out of the loop on the fact that radio news was rising in popularity. There was a niche market blooming in quick, short news briefs for ears instead of eyes and Betty saw an opportunity to be a part of it.

Since Betty was the only correspondent in the Scandinavian region, she was recording and filing her own reports for CBS and being paid on a weekly basis. But quickly, CBS determined that Betty’s voice was a problem (too light, too feminine, too high in pitch). It was believed, even in times of war, especially in times of war, that radio listeners didn’t want to hear a delicate voice reporting on death and destruction. Her reporting content was strong though, so CBS said that she had to find a male counterpart to step in as the voice in front of her work.

Betty was upset that she couldn’t speak the words that she was writing, but she wanted to keep her job, so she trained Winston Burdett, an American newly arrived in Stockholm, in the art of journalism for a radio audience, and he read her reports for her. Incidentally, she trained Burdett so well that she wound up working herself right out of Sweden. Burdett was after all a man and now (thanks to Betty) a good broadcaster.

Trying to find another unique vantage point like she had in Stockholm, Betty went to the Balkan Islands, and to Turkey before settling in Greece where she again sent reports home to CBS. Again, CBS said she needed a male counterpart to vocally relay her stories. And again Betty complied, this time working with a male Embassy secretary, who, at least, introduced himself on-air as “Phil Brown speaking for Betty Wason.”

As the Nazis occupied Greece, Betty’s bravery was called upon again as she reported eyewitness occurrences on a regular basis through her Embassy mouthpiece. While there, she endured house arrest under Nazi supervision for two months before the regime flew her and several other journalists to Europe for questioning. Concerned that Betty might be a spy, the Nazis detained her for an additional week by herself before eventually allowing her to fly back home to the US, where she was greeted with fanfare for having endured captivity and detainment.

Invigorated by the attention she received upon returning home and by the contributions she had made to broadcast journalism overseas, Betty naturally went to the CBS offices in New York to inquire after more work or a new assignment. Shockingly, executives at CBS refused to acknowledge that she played any significant part in the broadcasting realm overseas and denounced her requests for more story assignments. In an instant, Betty was dismissed like she had never been a part of the reporting team in the first place. Immediately, her work was marginalized even though CBS had been using her content repeatedly throughout the war, finding it valuable enough at the time to pay her for it. But upon Betty’s return, none of that seemed to matter. Had Betty been a man she would have been offered a position like Winston Burdett or handed a new assignment and sent to another corner of the globe. She would have been encouraged and supported by her colleagues and eventually been able to dispel the ridiculous notion that women couldn’t vocally report the news. But that didn’t happen.

After being turned away by CBS, Betty left New York and went on to Washinton DC, where she joined forces with other women in broadcasting, collaborating on various news shows and continuing on with her writing. Those few years of dangerous foreign reporting and her budding career of broadcast journalism didn’t turn out the way Betty expected, but ultimately, good things came out of this redirection in her life. Her ability to believe in her own talents and to creatively work around roadblocks with persistence and perseverance led her to a fulfilling career as a writer, on her own terms.

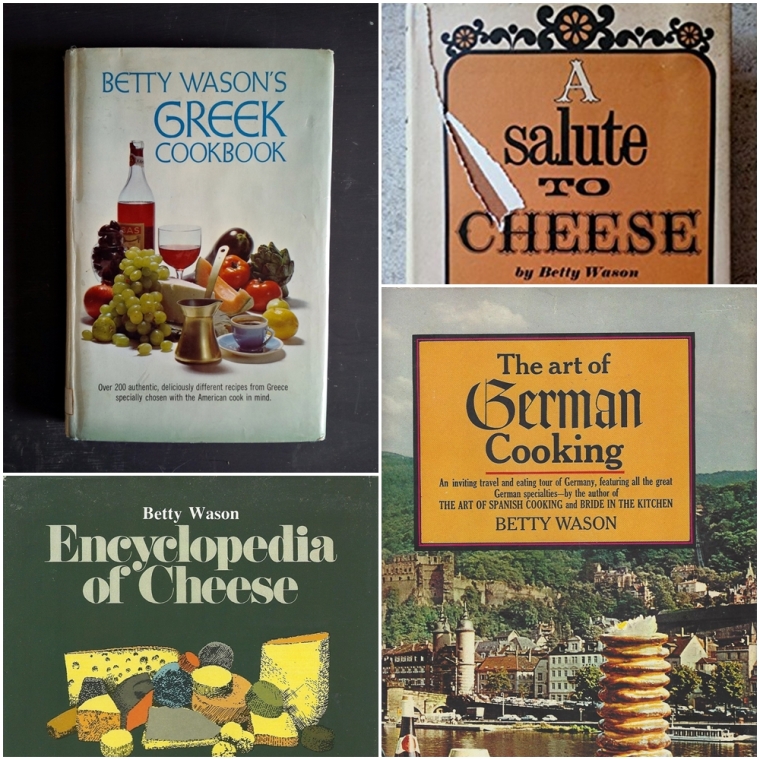

Inspired by her travels and her curiosity to learn more about local cultures and customs, Betty was devoted to exploring the history and the food scene in all the countries she visited, each eventually yielding their own distinct cookbook. Through her explorations in The Art of Spanish Cooking, The Art of German Cooking… of Vegetable Cooking… of Mediterranean Cooking… Betty wanted readers to experience the sights, sounds, smells, and tastes of her favorite places. That genuine, awestruck wonder led to over 20 beautifully written books that pull readers (and home cooks!) in from page one…

How I wish I were about to fly to Greece again, to relive once more that special thrill of seeing from the sky the ragged ochre shoreline with its-jewel-like border of turqouise merging into the royal blue of the Aegean…(from the introduction of her Greek cookbook)

In the Vintage Kitchen, we were introduced to Betty through her Greek cookbook simply titled Betty Wason’s Greek Cookbook, a stained and splattered edition worthy of its adventurous war correspondent author.

If a cookbook could ever be a travel guide, it would be Betty’s style of approaching food. Not only does she include authentic recipes, but she writes about them with the eye of a curious tourist learning a country in detail. In her Greek Cookbook, published in 1969, in addition to 200 recipes, she also included a state-by-state reference guide on where to buy authentic Greek ingredients in the US, a glossary of Greek terms, and special tips and tricks to make sure that the cooking experience remained as easily replicated as possible.

Yesterday, it was Betty’s birthday and today it is International Women’s Day. We couldn’t think of a better post to publish than this one on the forgotten lady of broadcast journalism and now the remembered author of important vintage cookbooks. In celebration, we made her recipe for Spanakopeta from her Greek cookbook. With spinach now coming into season, it is an ideal dish for Spring and a guaranteed crowd-pleaser for upcoming holidays like Easter and Mother’s Day. If you have never had Spanakopeta before, it is similar to quiche…. a mixture of cheese and spinach and herbs stuffed between two layers of phyllo dough.

It’s light in texture and constitution so it can be enjoyed as a side dish or a small dinner or a brunch accompaniment. Betty suggested that it could be served hot or at room temperature, which makes picnic basketing an option too. It reheats well and can sit in the fridge for a few days without getting soggy so if you are a make-ahead meal planner this recipe will be effortlessly easy and valuable.

Betty Wason’s SPANAKOPETA

Serves 6

12 phyllo pastry sheets

2 pounds fresh or frozen spinach (we used fresh)

1 teaspoon fresh dill, minced and chopped

2 tablespoons fresh parsley, minced

Salt to taste (optional)

2 eggs

1/2 lb. Gruyere-type cheese, feta cheese or dry pot cheese (* see notes)

1/2 cup melted butter or olive oil (we combined 1/4 cup of each)

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

If frozen spinach is used, cook as directed on package and drain well. If fresh spinach is used, wash and clean the leaves to remove any traces of dirt and pat dry. Heat a large saucepan over medium-high heat. Do not add any butter, oil or water to the pan. Working in batches, add as many large handfuls of spinach as will fit reasonably in the pan and toss with a wooden spoon until all spinach is wilted (about 2-3 minutes per batch). You may have to do this step in several batches depending on the size of your pan. Spread each cooked batch of spinach out on a cookie sheet to cool.

Once all the spinach is cooked, it will look like this…

At this point, you’ll need to wring as much water out of the spinach as possible. The easiest way to do this is to grab clumps in your hand and wring them out forming tightly packed meatball-like shapes. The drier the spinach the better so wring as much water out as you can.

Next, on a cutting board roughly chop each of the spinach balls. Mix in the dill, parsley, and salt to taste and toss until combined. I found there to be enough natural salt in the spinach and the cheese, so we didn’t add any extra salt to this dish at all, but season it to your preference.

Add one egg to the spinach and herbs and toss to combine. Grate the cheese. We can only find Gruyere at our grocery store occasionally, so I used Danish Fontina which is similar. Other options are Jarlsberg, Swiss or Feta.

Add the second egg to the grated cheese and mix to combine.

Butter a square 9×9 baking dish and place 6 sheets of phyllo pastry in the bottom. Brush each sheet with the olive oil and/or butter. Then add the spinach, and top with the cheese.

Cover with six more sheets of phyllo, each brushed in butter/olive oil. Don’t forget to brush the top layer.

Bake in a 350-degree oven for 35 to 40 minutes until pastry is golden. Remove from the oven, let cool until the dish can be handled,

then turn out upside down on a baking sheet and return it to the oven so that the undercrust can become crisp and golden (about 15-20 minutes).

Remove from the oven, flip back over and cut into squares. Serve while hot or wait for it to cool to room temperature. We served our spanakopeta with a glass of sauvignon blanc and a simple side salad tossed in olive oil and lemon juice. Other additional sides that would be lovely with this include hard-boiled eggs, olives, mixed nuts, prosciutto, or roasted sweet potatoes.

Light, airy, and full of subtle flavors that are a little bit nutty (the cheese), a little bit zesty (the herbs) and a little bit earthy (the spinach), Betty’s spanakopeta is packed full of good, healthy nutrients, providing a simple introduction to the lovely world of Greek food.

It’s a good-for-your-spirit food mirroring Betty’s healthy outlook on life. She cast aside all the bitterness and resentment that could have filled her up in the post-CBS days and instead stuffed her life full of light, bright joy that enriched her spirit and fed her soul. Cheers and happy birthday to Betty for continuing to inspire women around the world with your writing.

Interested in learning more about Betty and her Greek recipes? Find her cookbook in the Vintage Kitchen shop here.