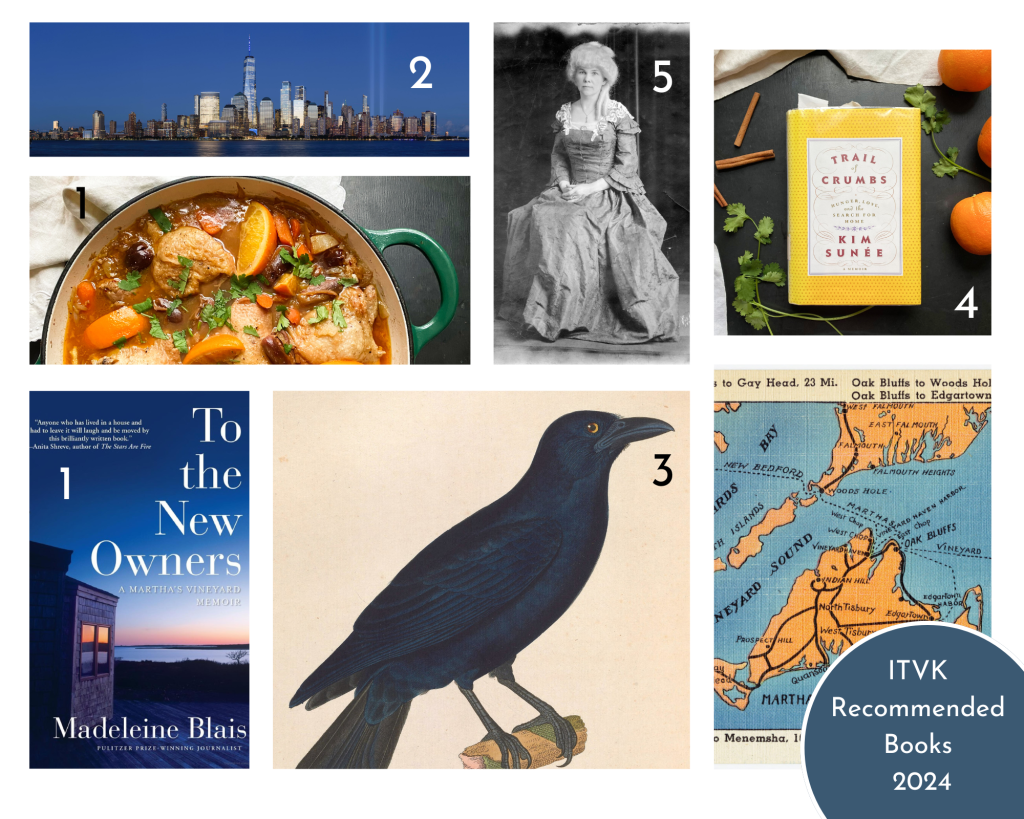

When December comes around every year, I always love compiling the book list. This month marks the end of 2024, and also the start of the wintertime reading season with the release of the annual Vintage Kitchen recommended book list. Blog stories were a bit sparse this year due to many unanticipated factors, but I’m happy to say that they haven’t hindered this annual tradition of posting a collection of favorite books discovered throughout the year.

If you are a long-time reader of the blog, you already know that these lists are made up of books that were serendipitously found over the course of the year while doing research for Vintage Kitchen blog posts, shop stories and recipes. Every year, they cover a range of subject matters and time periods, and span a range of publication dates from new releases to books written decades or even centuries ago. As an avid reader, averaging about 30 books a year, I save the most beloved ones for this list. The ones that left an indelible mark, or sparked some new inspiration, or offered a different perspective on a subject matter already familiar. These are the books I couldn’t put down. The ones that I still continue to think about long after the last page is read.

This year’s selection is varied in content but they do have an underlying connective theme of gratitude and appreciation. There’s a book about nature, a book about a summer vacation house, and a book about American life lived three hundred years ago. Three of the books this year are memoirs, one book contains recipes, and unlike last year’s list, all five of these books are non-fiction. They tell bittersweet stories of friendship, of being present in time and place, of establishing traditions, and of searching for meaning in everyday life. These five take us around the world from coastal Massachusetts to New Orleans to New York City to Paris, Stockholm, South America, and to our own backyards. One book even helped solve a mystery about the floorboards of 1750 House. Interesting adventures await on all fronts.

Let’s look…

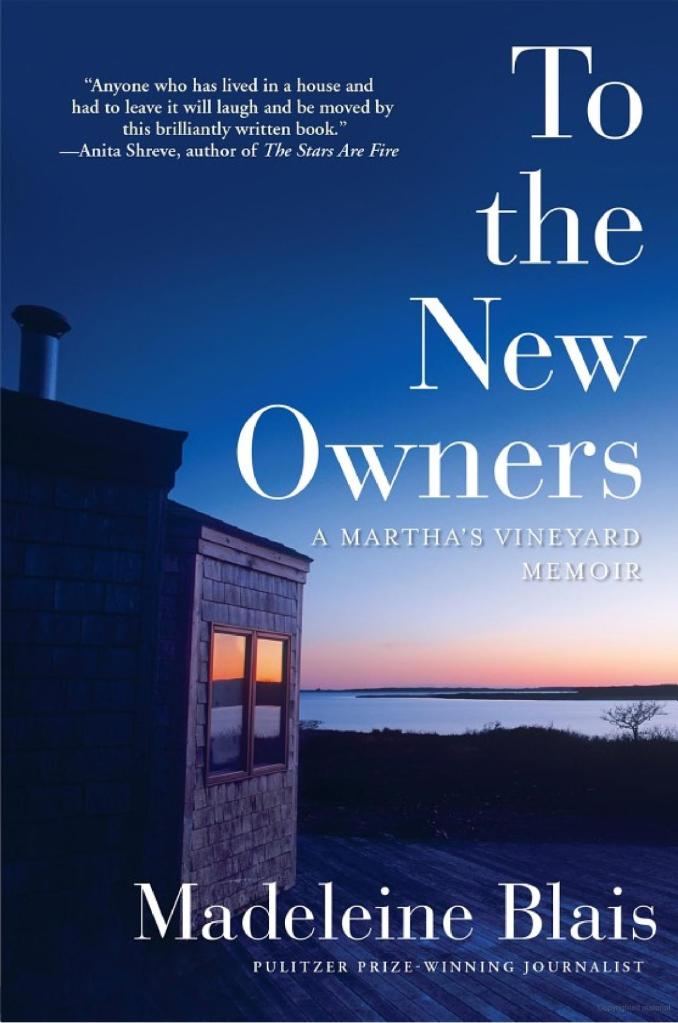

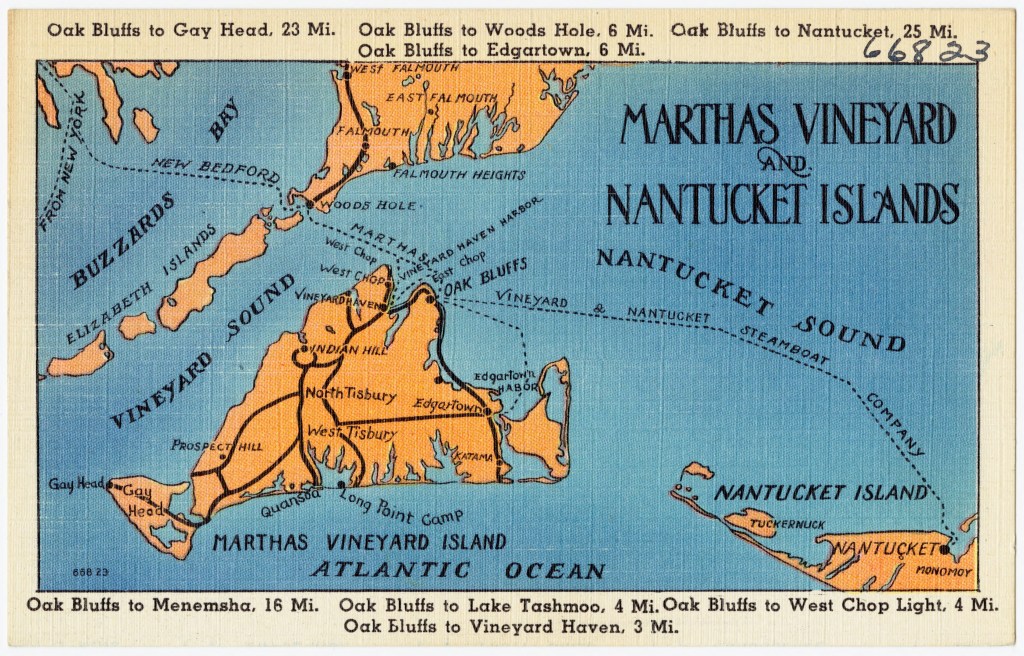

To The New Owners – Madeleine Blais (2017)

A love story to summer. To family. To a seasonal beach house on the shore of Martha’s Vineyard. To the New Owners is one long anticipated string of summer sequels highlighting vacation life spent in coastal Massachusetts. Written by Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Madeleine Blais, who married into the enigmatic and literary Katezenbach family, this memoir starts off with news that the beloved beach house, the family vacation compound for five decades, is going up for sale.

You might suspect with a topic like this that what could follow is a sappy cliche. A backward look at a family home where frivolity, relaxation, and low expectations were the driving force behind each summer. A book chock-full of events and experiences only interesting to the people who actually experienced it. That’s not the case here.

While there is certainly sentimentality and a true loyalty to the land and its residents, both seasonal and year-round, this memoir reads like an engaging conversation shared over a lengthy dinner party. It is full of quirky characters, funny stories, interesting history, and an undying love of the written word.

From record-keeping log books to island newspaper articles to Madeleine’s own accounts of house repairs, family dinners, environmental changes, historical events, and all the people and pups that marked their time on the island, this is a memoir of Martha’s Vineyard not from the glitzy, multi-million dollar mansion perspective, although there is mention of that too, but from a rowdy, vivacious, thrifty, unpretentious contemporary family viewpoint. The type of living that represents the true spirit of the island and its origins. And in the case of the Katezenbach family, a lifestyle that respected the power of words over the power of the pocketbook.

When she first shows up to the Vineyard, Madeleine doesn’t exactly know what to expect. She knows nothing of the island, or the people she’s going to stay with, or the type of lifestyle that requires a summer residence and a winter residence. But she does have an imagination. And what she pictures in her mind on the way to her first visit to the summer house is not the almost dilapidated shack that she encounters. Rustic is what her husband called it, a far cry from the multi-million dollar estates that dot much of the M.V. coastline. Intrigued by the island’s humble roots and the glamour it was later associated with, Madeleine explores the history of the island, her new family, and the literary-loving community that it reflected all through the lens of the summer house.

Funny, wise, poetic, and relatable whether you’ve ever had the experience of summer beach house living or not, Madeleine’s memoir is about love, loyalty, nature, pride of place, and acceptance of what is, as it is. A look at an island that boasts extremes from all directions including wealth, prestige, celebrity, notoriety, and eccentricity, but also sandy kitchen floors, wet dogs, leaky roofs, fishless-fishing trips, thwarted dinner invitations, spectacular sunsets, faulty wiring, stunning beaches and the whole mess with the nearby pond that affected everybody.

At the heart of the story are the log books – the fortuitously started notebooks that hold random journal entries of all the small, everyday details that make up life at the beach house for fifty summers. Sporadic and eclectic, with contributions by family members and visiting guests, the log books were available to anyone staying at the house who wanted to note something, anything. The first log book started what would become a tradition and then ultimately a treasure trove of notes and musings on recipes, house improvements, weather, linguistic games, family health, poems, housecleaning tips, recommended book lists, pet antics, children’s drawings, island events, and conversational interactions with town locals. No one particularly thought that the first log book was going to turn into something special, but when it was full and there were no pages left to record anything else, another book was ordered and filled again, and over and over it went for five decades.

Having that kind of family detail available helped Madeleine paint such an intimate look at life on Martha’s Vineyard that by book’s end you’ll feel like a local yourself. What’s particularly lovely is how everyone truly appreciated the house, the parcel of land it sat on, and the exposure to nature that it provided them. Across all the fifty years, any one guest, family member or otherwise, who couldn’t appreciate this slice of paradise or didn’t see the charm of it all wasn’t invited back the following year. So the summer house became a club-like haven of love and joy and appreciation and fulfillment even on the leaky roof and the fishless fishing trip days. It chronicled the years of a couple’s marriage and embraced the outpouring of their offspring. It sheltered three generations, countless friends, family pets, and invited guests. And then the inevitable happened. Life changed. And with it, the bittersweet goodbye to fifty years of what once was.

Grief Is For People – Sloane Crosley (2024)

Just as there are many stages of grief there are many things in the world to grieve. In this book, Sloane Crosley grieves two real-life events simultaneously… the suicide of her best friend and the theft of family jewelry from her NYC apartment. Both incidences occurred within 30 days of each other. Both were a shock to the system. And both left Sloane at a loss confronting major thoughts and feelings about each situation.

You might suspect that the death of her dear friend would take precedence over the theft of jewelry she inherited from a grandmother that no one really liked, but Sloane is an incredible storyteller and manages to give equal emotional weight to both scenarios while also offering an interesting behind the scenes look at the publishing industry that she and her friend were very much a part of for over two decades.

Grief Is For People is, yes, a book about grieving but it’s also a memoir of a specific time period in Sloane’s publishing career, a portrait of a friendship, a writer’s coming-of-age in the big city of New York, and the emotional value of inherited objects. It’s humorous and insightful, smart and sincere. It’s full of grit and determination to right the wrong of burglary while also bravely sorting through what it means to love, rely on, appreciate, and remember someone who was here one minute and gone the next.

Sloane shares this story in a captivating timeline of events. So as not to spoil the pacing, I won’t say anymore other than that if you are new to Sloane Crosley and her work, I’d also highly recommend her 2008 book of essays I Was Told There’d Be Cake.

The Comfort of Crows – Margaret Renkl (2023)

Stop and look. Those are the first three words of Margaret Renkl’s ruminations on nature and her year-long accounting of it in The Comfort of Crows. Written from the vantage point of her backyard in Nashville, TN and a friend’s nearby vacation cabin in the mountains, Margaret writes about the sights and sounds of nature witnessed firsthand over the course of a calendar year. In brief vignettes accompanied by her brother’s beautiful illustrations, Margaret draws attention to common occurrences happening with the birds and the squirrels, the trees and the bees, the plants and the pollinators, week by week, while also reflecting on her own life and the parallels these natural encounters draw.

Part nature study, part memoir, part call to action, I would recommend The Comfort of Crows to anyone who wants to unplug from the outside world for a weekend, a week, a month, a year. If you need a break from social media, the news, the what-ifs, and the how-to’s, this book is easy to fall into. Calming, thought-provoking, and comforting, it offers a gentle reminder that in nature there’s a plan, a purpose, and a resourcefulness that is indefatigable, adaptable, and inspiring.

Stop and look. Stop and listen. Stop. Look. Listen. See. Hear. These are simple words that yield powerful insight into the dramas, destinies, and determinations going on in everyday life around us. Whether it’s the backyard, the city park, the country meadow, the forest, the beach, or the planting strip in the parking lot of your local grocery store, there’s insight to be gained from the creatures that inhabit these parcels of place.

Starting on Week One, the first of January, Margaret shares in her lovely, poetic voice how nothing is actually dead even in the dead of winter. “Everything that waits is also preparing itself to move,” she notes. “The brown bud is waiting for its true self to unfold: a beginning that in sleep has already begun.”

I can’t really describe this book as anything other than an experience. It’s heartwarming and serene, playful and curious, sentimental and sad. It is fun facts and first-hand observations. It’s a love letter to what is and a longing to change what might become. It’s a book. It’s short stories. It’s prose and it’s poetry.

Conscious of global warming and human impact on the natural world, Margaret is hopeful that we can right the ship and learn how to cohabitate with plants and trees, insects, and animals in order to encourage a beneficial landscape for all instead of just some. In acknowledging that we have collective work to do in that regard, this book carries its own bittersweet narrative – an appreciation of what is here now but a realization that it might it not be here in the same way tomorrow. That viewpoint automatically sets the tone for awareness which is the overall theme of Margaret’s year. To be aware of one’s natural surroundings. To be aware of what is in one’s natural surroundings. To be aware of the wild in the world. It’s that recognition that Margaret hopes will propel you out into the greenspaces of your life. To look and to see. To hear and to help. All, so that we can continue to hope.

Trail of Crumbs – Kim Sunee (2008)

Abandoned in a Korean marketplace when she was three years old, Trail of Crumbs follows the real-life of Kim Sunee from toddlerhood through her late twenties via place, people, and passion. Adopted into a well-meaning American family and taken to live in New Orleans, Kim’s presence in the world from the beginning never quite clicks. Seesawing between feelings of gratitude and abandonment, she grows up out of place as an Asian American in the Deep South. Carrying the emotional baggage of a person who has been left behind, Kim is too young to put words to her lost person emotions.

As a child, the only place she finds real comfort is in her grandfather’s kitchen, watching him and helping him cook an array of Southern specialties. This early introduction to the internal power of food becomes Kim’s barometer, her measurement of what feels right and wrong in her life, of what is fitting and falling apart around her. Cooking becomes the bridge that connects her with a cast of characters that come in and out of her life, leading her around the globe over twenty years in search of the definition of home, both internal and external.

With every new person she meets, every new relationship she begins, her life pivots. She makes friends with artists and writers. She teaches English classes to foreign children. She writes poetry. She translates business brochures. She runs a bookshop. All the while searching for her true self.

In all these people, all these places, all these jobs, Kim tries to move on from being left behind. She tries to make peace with her past and the mother who left her on a bench in a market with just a fistful of crackers. She goes to Paris. To Sweden. To South America. She eats, drinks, and cooks in new kitchens of new friends, new lovers, new neighbors. In France, she meets and falls in love with a high-profile businessman who is determined to give her everything she ever wanted. For a time, this romance is ideal. A fairy tale in the making with affable rom-com pacing. She’s finally met someone who is ready to unclasp her fingers from the tight grip that carries her emotional suitcases. He wants to give her everything she never had. A fresh start. A new life. Her own making.

But as much as they love each other, and as passionate as their relationship is, it’s also fraught with complications. Kim questions this knight-in-shining-armor and her worthiness of him. She wears the invisible letter L for leaveable like a badge that defines her. And in believing that she’s leaveable she can’t ever truly stay anywhere. That creates a restlessness that no amount of kindness, no amount of money, no amount of love, or attention, or security can cure until she learns to love herself for herself.

Along with this search for peace and family, Kim’s memoir is dotted with recipes throughout, each one representing a different aspect of her physical and emotional journey from childhood to adulthood. There are recipes that reflect her Korean heritage, her Southern upbringing, and her love of French food. There are recipes for snacks, comfort foods, fancy dinner parties and elegant desserts. Each one, a place marker of her growth and development. They represent comfort in times of unease and joy in times of safety and security. There are so many truly lovely-sounding recipes in Kim’s book that I practically tagged each and every one. In the next blog post, we’ll be delving into one of her recipes from Trail of Crumbs – Chicken Thighs with Cinnamon and Dates – which appears about halfway through her story when she’s in the middle of her French love affair. Stay tuned for that post coming shortly.

The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in Colonial America from 1607-1783 – Dale Taylor (1997)

This is pretty niche reading, and I realize not everyone may be as curious about colonial life as we are here at 1750 House, but this book provides so much interesting, little-known information on domesticity in the 17th and 18th centuries, it will appeal to history lovers of all sorts on all levels. Covering architecture, clothing, occupations, gender roles, homekeeping, agriculture, professions, education, religion, and government, I came to this book initially interested in reading the chapter on architecture in hopes of learning some new information about 1750 House, but the whole book turned out to be captivating and I flew right through it.

Brimming with all sorts of very fun fun facts, historical interpreter Dale Taylor wrote this book specifically for writers so that they would have an accurate understanding of the all details that made up real life in the colonial era. With that audience in mind, Dale includes an array of anecdotes that help bring history alive in a relatable way. It’s also a great resource when solving floorboard mysteries.

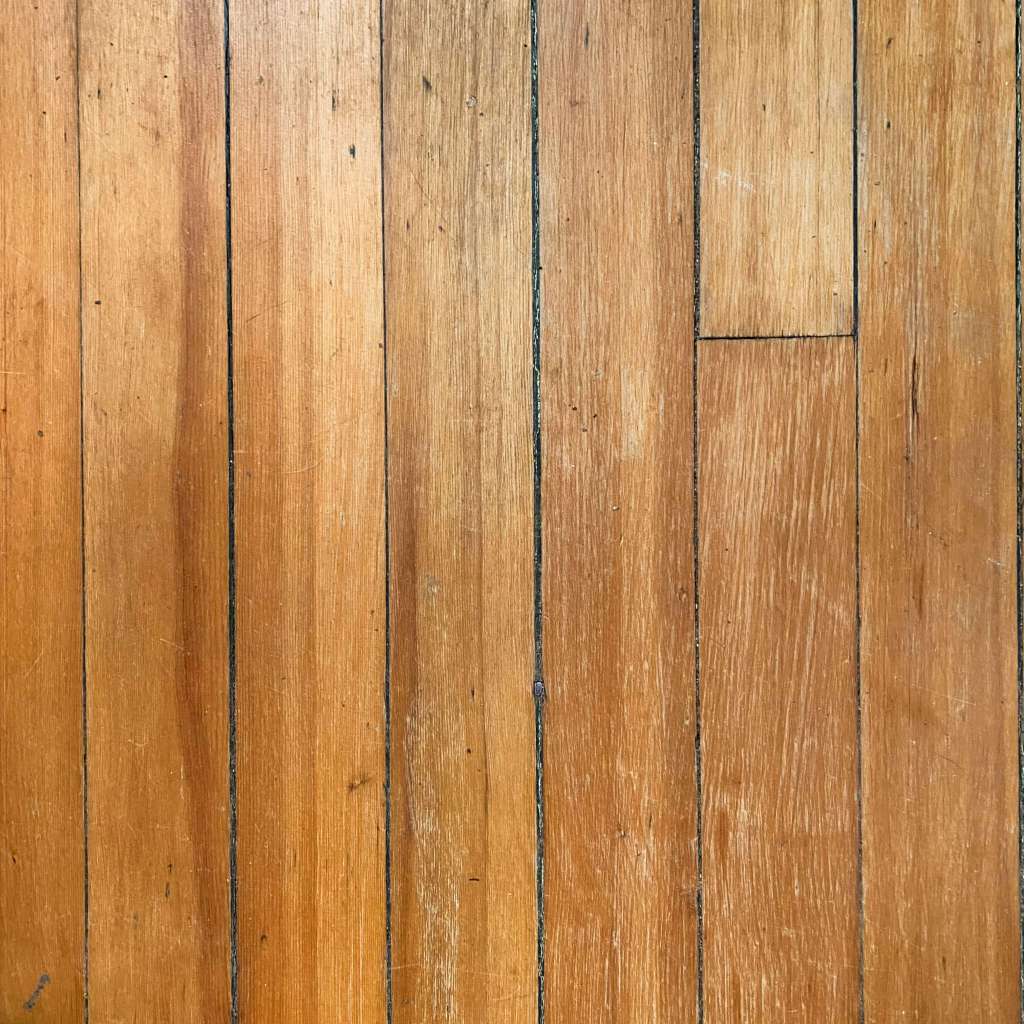

Upstairs in 1750 House, the original wide plank wood floorboards which are made of solid 3″ inch thick chestnut, measure between 9.5″-15″ inches in width per board. But downstairs, the wood floors are much narrower in width, about 3.5″ inches on average.

This has always led to curious conversations about why the floorboards aren’t the same on each floor. We suspected that the downstairs floors were replaced at some point later in time, possibly in the mid-1800s when the kitchen room was added. But come to find out, according to Dale, in colonial days, wide plank boards were less expensive to mill, so they were often used for flooring in the more private rooms of the house, which tended to be on the second floor or at the back of the house on the first floor. The narrow-width floorboards were laid in the front of the house on the first floor in the parlor rooms. These narrow boards acted as a status symbol letting visitors know that the family who lived there could afford such luxury. In the case of 1750 House in particular, this newly learned information makes a lot of sense.

Not long after we moved in, we learned about the architectural significance of the front door, which is also original to the house. In the photo below, you’ll notice four small windows that are built in at the top of the door. During the colonial era, that was another bit of luxury – to be able to afford glass in your front door. The panes not only allowed extra light to illuminate the interior but there was also religious symbolism attached to them too. Religious colonists believed that by installing windows at the top of the door, it allowed God a peek down from the heavens to make sure there was nothing improper going on indoors. Just like the original H-Hinges found throughout, it’s another little bit of unique symbolism that lives here. And thanks to Dale’s book, it now gives us a better understanding of the economic status of the original owners of the house.

Architecture notes aside, other types of fun facts that can be found in Dale’s book include these little marvels…

- Pets during the colonial era included dogs and cats, but not birds. Birds would not be kept animals until the Victorian era. However, squirrels and deer were also common pets in colonial days and the deer were allowed free reign both inside and outside the house.

- Bearskin rugs were the first indoor fire alarms. In the 17th and 18th centuries, they were laid out in front of the fireplace in case an errant ember flew or a log rolled out into the room. At night, after the household had gone to bed, if an ember sparked or a log rolled out, the rug was the first point of contact. It would begin to smolder, emitting the smell of burnt hair. That smell would awaken people in the house and signal that there was a fire near the fireplace which could be easily and quickly be put out because of the rug.

- 25% of women’s deaths in colonial days were due to life-threatening burns caused by cooking in an open fireplace. That led women to start hoisting up their skirts and tucking them into the waistband of their dresses in order to avoid catching the hems on fire. From that point forward, the kitchen was viewed as an indecent place to spend time and the staff that worked in them were viewed as having low repute.

- Since cloth was one of the costliest items in colonial America dresses were made to last for 15 years which means that some women owned only about 2-3 dresses in their lifetime.

- Wigs were commonplace for men and women in colonial times, but the super tall and lofty wigs were only worn by women in big cities like Philadelphia. These wigs were so elaborate in design, style, and augmentation that they were often worn even at night while sleeping. This full-time, overnight headress necessitated arrangement in such a way to accommodate mouse traps since they were made of natural nesting materials.

- In 1752, the celebration of the new year was moved from March 25th to January 1st, which of course, has stayed the same ever since.

Reading is so subjective when it comes to personal preference. Everyone has their own favorite styles, writers, and genres, but I hope by sharing my list of favorites, you’ll discover some new favorite ones too. Stay tuned for a recipe I just made from Kim Sunee’s memoir coming up next on the blog. It’s an aromatic, cozy, wintertime dinner that is absolutely lovely for the holidays. Here’s a sneak peek…

Until then, happy reading! And a big cheers to Madeleine, Sloane, Kim, Margaret, and Dale for making 2024 such an interesting one.

Wonderful recommendations! Thanks for the list.

LikeLike

Oh thank you Dorothy! If you get a chance to read any of these, please share your thoughts. It would be so fun to start a little book club:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would!

LikeLiked by 1 person