It’s just the start of 2024, but here in the Vintage Kitchen, there is a finish line coming into view. This year we will be wrapping up a five-year project that first started here on the blog in 2020. I’m so happy to say welcome back to The International Vintage Recipe Tour.

What started out as an intended year-long project of cooking 50 recipes from 45 different countries in 2020 has now taken five years to complete just to the halfway mark. A pandemic, a tornado, a big cross-country move and 1750 House renovations have waylaid plans far more than ever anticipated, but this project has always been such a joy I never wanted to not finish it. So here we are, at the start of 2024 finishing things up from 2020.

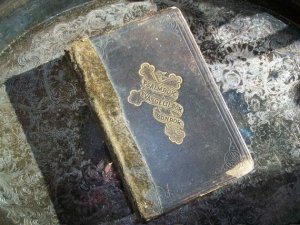

For a quick recap and for anyone new to the blog, The International Vintage Recipe Tour takes home cooks and readers on an around-the-world adventure via the kitchen, as we cook our way through a collection of recipes featured in the 1971 New York Times International Cookbook.

Throughout the Tour, we are visiting 45 countries via the kitchen and making at least one traditional heritage food from each, sharing both the recipe and the cooking experience here on the blog. To add context to the food we are making, and to spark some new conversations around the table, every visit to a new destination is paired with a unique cultural story from that country’s history.

So far we’ve visited twenty-four countries via the kitchen on this tour… Armenia, Australia, Austria, Barbados, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Ceylon, China, Colombia, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Dahomey, Denmark, England, Fiji, France, Germany, Greece, Haiti, Hungary, India, Indonesia, and Israel. It’s been a whirlwind of fun, friendship and delicious food.

We chatted with an author and a food columnist via Armenia, met a descendant of the designer of the Statue of Liberty via Germany, and embraced our inner bula in Fiji. We discussed tropical architecture in Haiti, made floating paper lanterns to celebrate the Hungry Ghost Festival in China and donated funds from shop sales to help save the koalas injured in the Australian wildfires. We discussed women’s fashion in India, interviewed a Cuban-American farmer in Miami, and learned about a long-lost African-American dance in Dahomey. On the food front, we curried in Ceylon, baked Queen Mother’s Cake in Australia, made homemade mustard in Denmark, learned that not all fondue comes in a hot pot in Belgium, and took a much-needed virtual vacation to Corfu via Greece.

Our latest stop on the tour was Israel, which lined up with the 2021 holiday season. To celebrate we made a Hannukah wreath, cooked two recipes for dinner, and dove into the history of both the Jewish flag and the Jewish star. Now, our next stop on the International Vintage Recipe Tour takes us to Italy, one of the most beloved cuisines in the world. Here we’ll make a provincial meal meant for sharing and meet an artist whose family recipes formed the basis of a life-long passion with food. Welcome to Italy.

It’s impossible to write about Italy without writing about family. And you can’t write about this recipe, Chicken Canzanese without writing about a specific family. Like France and China, Italy is one of the largest chapters in the New York Times International Cookbook. There are literally dozens of recipes to choose from, a switch from some countries that had less than a handful.

Besides the long wait to get the Tour started again, the hardest part about starting up again with Italy was which recipe to choose and which cultural treasure to spotlight. Contenders in that department were Stanley Tucci’s gorgeous Searching for Italy show, the multi-generational novel The Florios of Siciliy and the genealogy of the love apple (aka the tomato). There were all the pastas and all the sauces, lovely vegetable side dishes, and quite a few desserts to pick from, but the recipe that I kept coming back to was a one-pot chicken dish that was credited to an artist.

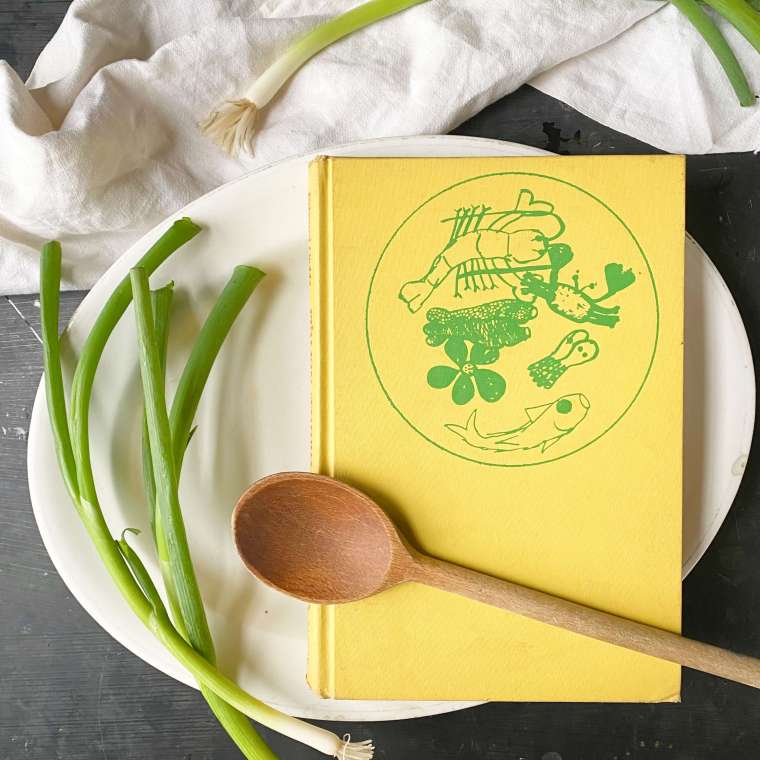

Last fall, while visiting a local bookshop, I discovered a bright yellow 1970s Italian cookbook. To my sheer delight and surprise, it was written by the same artist mentioned in the New York Times International Cookbook. A quick peek inside revealed the same exact recipe that was also featured in the NYTimes cookbook. The same recipe by one artist in two different books. It was a sign. This was the right Italian recipe for the Tour and the right time to tell a story about a creative spirit, who also happened to be an Italian cookbook author.

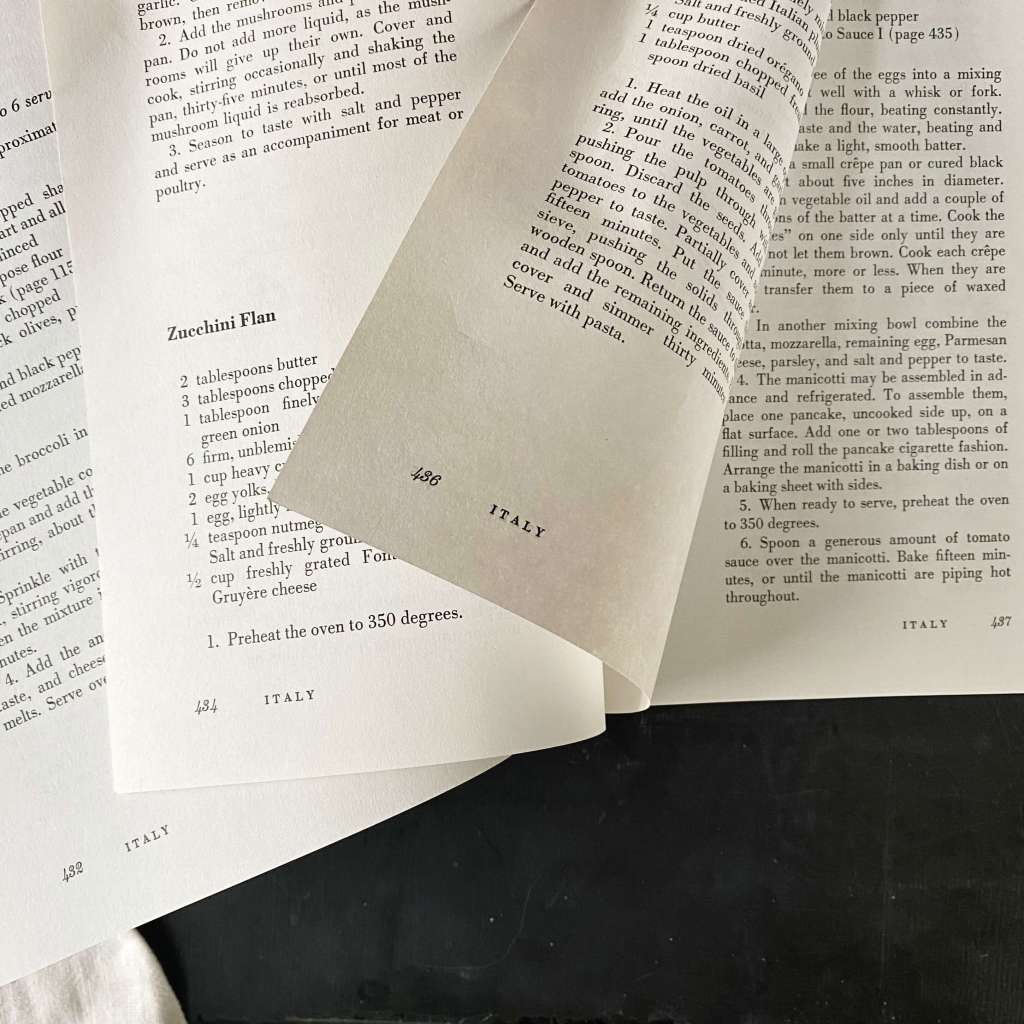

The artist is Edward Giobbi, a second-generation Italian-American born in Connecticut in 1926. Still painting today from his home studio in Katonah, New York, at the age of 98, Edward’s lived his entire life in pursuit of art and food. The book that made him well-known in the culinary world was his Italian Family Cookbook, first published in 1971. Selling over 30,000 copies by the 1980s, it offered home cooks a sincerity that resonated on multiple levels when it came to preparing economical and creative meals in true Italian style. The recipe featured here today, the one that appears not only in Edward’s cookbook but also in the New York Times International Cookbook, is his Chicken Canzanese, a slow-simmered one-pot made of chicken, herbs, wine, spices, and prosciutto.

A lovely selection for these end-of-winter days when the weather is jockeying back and forth between spring-like temps and snowstorms, this recipe is both light and hearty, depending on the sides that accompany it. It’s easy to prepare, has a warm, rich, earthy fragrance thanks to the prosciutto, garlic, and herbs, and can definitely be labeled a healthy comfort food since it contains no added fat.

The cooking prep is also interesting. There is a cold water brine, a unique set of flavor pairings, and a few very precisely measured spices… twelve peppercorns… six whole cloves… two sage leaves. I always find precise measurements like this fascinating. What was the process that a cook went through to determine that perfect balance of six versus seven cloves or nine versus twelve peppercorns? Would three sage leaves as opposed to two send the whole meal over the edge?

As it turns out, Edward’s style of cooking and how he first learned it was based on quality but also frugality. Growing up during the Great Depression taught him and his family the value of growing your own food and utilizing agricultural resources close to home. Nutrition was key to keeping everyone healthy. Nothing was wasted or under-appreciated. Every bit of joy that you could scrape from an experience mattered. As an adult, Edward approached food in much the same way.

In the NYTimes cookbook, the recipe for Chicken Canzanese is simply attributed to Ed Giobbi, the artist. But in Edward’s cookbook, Italian Family Cooking, it’s attributed to Edward’s mother by way of a woman who lived in Canzano, in the Abruzzi region of Italy.

Located in the middle of the boot, Italy’s beautiful Abruzzi/Abruzzo region borders the Adriatic Sea and also the Apennines Mountains, both of which provide ample agricultural opportunity. Canzano is 105 miles east of Rome, and 230 miles southeast of Florence, and although geographically considered central Italy, the culture and food traditions of this area mirror that of Southern Italy.

Full of food specialties ranging from provincial fish soups to local lamb dishes to plates of handmade pasta the traditional foods of Abruzzo favor both its maritime and mountain environs. Incidentally, this area of Italy is also known for a food often consumed at weddings here in the US. It’s the birthplace of the pastel-colored, candy-coated Jordan Almond, also called Italian Confetti locally.

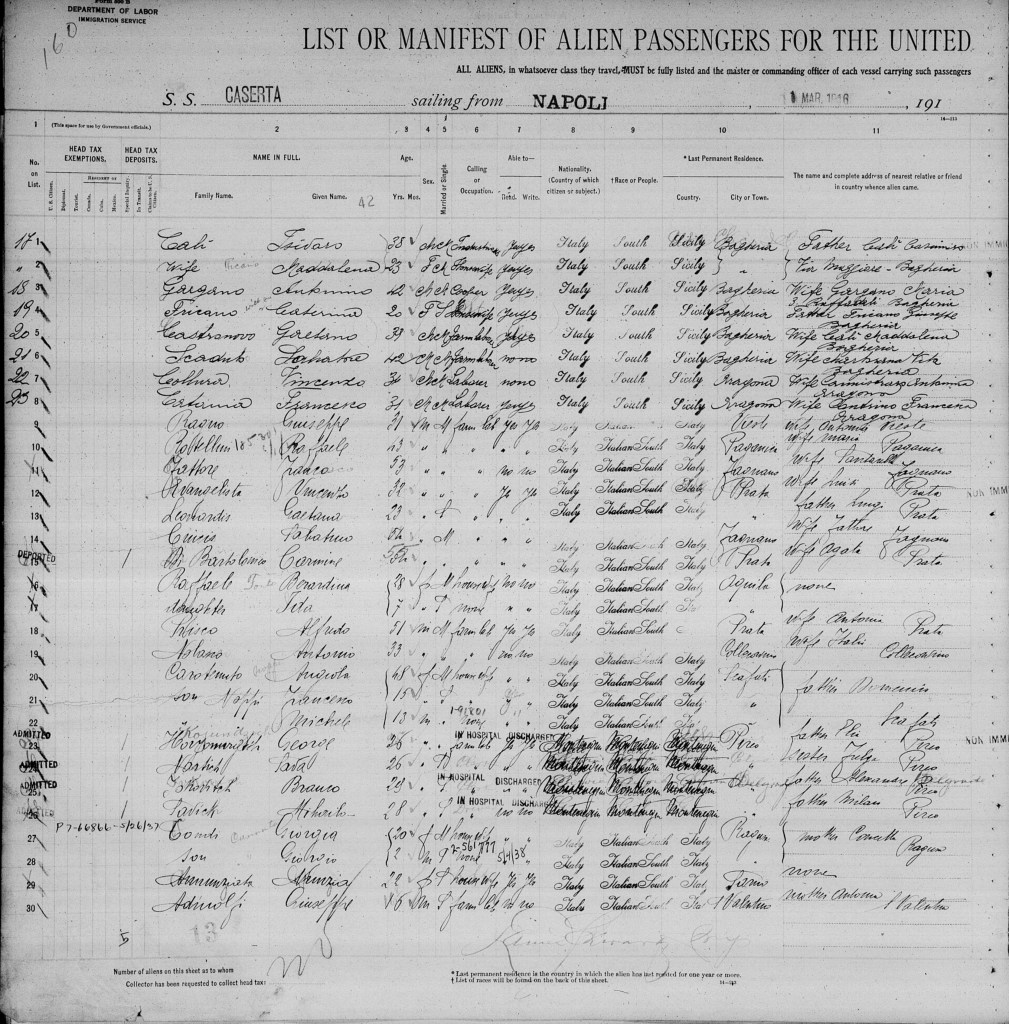

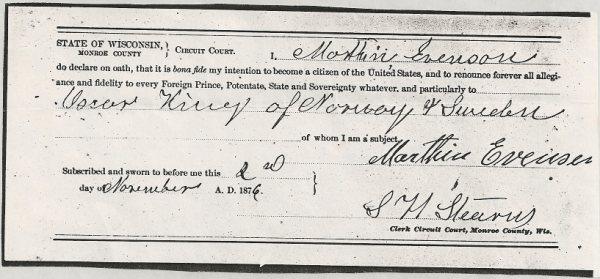

Edward’s parents immigrated to the US in the early 1900s first to Pennsylvania and then to Connecticut where they labored in factories and mills. Even though they both just had a third-grade level education, his parents had an appreciation for food, art and music which made a strong impression on Edward during his childhood. The Giobbi family kitchen would come alive at night and on weekends with the scents and flavors of his parent’s home country.

Once he left home to pursue his art, his mom’s heirloom recipes became a vital part of the creative process as he perfected each one in his own kitchen, practicing them over and over again, until they met her standards and his memories. That dedication to good food and good eating, combined with artistic sojourns to stay with extended family in Italy sealed his love of cooking indelibly.

By the time Edward married and had his own family, preparing daily meals was a pleasure equal to painting. In his children, he instilled a similar joy. Art and cooking became a throughline that ran strong in the new generation of the Giobbi family members.

Apart from the myriad of wonderful traditional Italian recipes in Edward’s cookbook, the illustrations stand out with vibrant appeal and eye-catching charm. The art was executed not by a hired freelancer or a publishing industry dynamo. It wasn’t executed by a professional food photographer or a graphic design studio. Instead, the illustrations for his cookbook were illustrated by a collection of painters entirely new to the world – his children, Cham, Lisa and Gena who at the time ranged in age from six to nine.

Edward gave his kids no direction when he asked them to paint pictures for the cookbook other than to say “draw a fish, or a soup pot or a bottle of wine.” Each of his artists offered their own interpretation.

Whimsical and sweet, Edward Giobbi’s Italian Family Cookbook was indeed, in all ways, a family affair from kids to parents to extended relatives. It didn’t stop at this cookbook either. Edward went on to write another successful cookbook, Eat Right, Eat Well: The Italian Way (1985) and his band of illustrators grew up to pursue their own careers in art, dance, music and food science.

In keeping with the Giobbi clan’s combined love of the kitchen, nothing seems more fitting than presenting this recipe on a Sunday night when family dinner rules the kitchen in most Italian households. Named for the town in which it hails, Chicken Canzanese is a meal intended for communal family dining. Simple to make, it’s a two-step process that involves a one-hour wet brine and forty minutes of cooking time. True to Edward’s nature and his mother’s style of cooking, it’s made of simple ingredients and offers a bevy of creativity in the side dishes in which you choose to serve with it. More on those thoughts follow the recipe.

Edward Giobbi’s Chicken Canzanese

Serves 4

One 3 lb chicken, cut in pieces

2 sage leaves

2 bay leaves

1 clove garlic, sliced lengthwise

6 whole cloves

2 sprigs fresh rosemary or 1/2 teaspoon dried

12 peppercorns, crushed

1 hot red pepper, broken and seeded (optional) or 1 teaspoon dried red pepper flakes

1/4 lb prosciutto, sliced 1/2 inch thin or one 4oz package of pre-sliced prosciutto*

1/2 cup dry white wine

1/4 cup water

Salt for brine (see note)

Place the chicken pieces in a mixing bowl and add cold water to cover and salt to taste. *Note: I used a large mixing bowl and 1/8 cup of sea salt to 6 cups of water. Cover with plastic wrap and store in the fridge for 1 hour.

Drain the water and rinse the chicken pieces completely before patting dry with paper towels.

Arrange the chicken pieces in one layer in a skillet. Add the sage, bay leaves, garlic, whole cloves, rosemary, peppercorns and red pepper. Cut the prosciutto into small cubes and sprinkle it over the chicken. *Note: If using pre-sliced prosciutto, remove all the paper or plastic sheets between each slice. Stack the prosciutto one on top of the other, and cube the whole stack at once.

Add the wine and water. Do not add any additional salt, since the prosciutto will season the dish. Cover and simmer 40 minutes. Once the chicken has cooked to an internal temperature of at least 165 degrees. Uncover and cook briefly until the sauce is reduced slightly. Serve hot.

Rustic and earthy, Chicken Canzanese is tender and full of subtle flavors. The broth itself is fairly salty on its own thanks to the simmered prosciutto, but soak it up with a piece of crusty bread, and the briny flavor mellows. There were no serving suggestions mentioned in Edward’s recipe nor the NYTimes, but the broth would be lovely tossed in a warm bowl of pasta, spinach, peas, potatoes or mushrooms. If you are feeling decadent you could add a dash of cream to the broth to balance all the flavors. As Edward says in the introduction…”Cook the food in this book with a free hand, using your own creativity with the freshest ingredients you can get.”

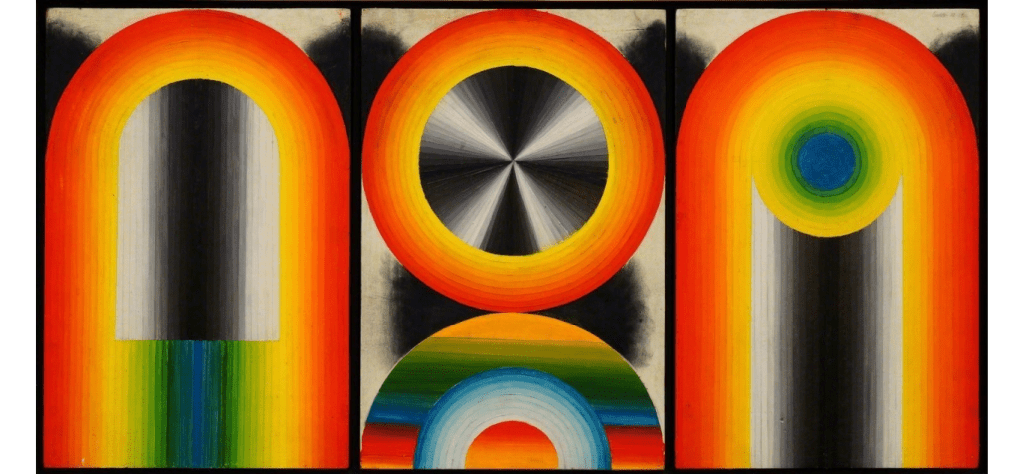

Collected by museums and galleries around the world, throughout Edward’s long art career his style has varied…

He dislikes labels or being lumped into a certain type of painting, but he one thing Edward consistently strives for in his art instead is honesty. The same could be said for his cooking. All of his recipes are celebrations of local eating. They reflect riding the highs and lows of economy, of balancing cooking constraints with bounty, and the importance of identifying local resources. His recipes are interesting, creative, nourishing. They are of the earth and of the moment. I think that’s what makes Italian food so appealing. It’s a cuisine rooted in a waste-not culture that appreciates what’s right there in front – all the bounty that the earth can offer.

My favorite piece in Edward’s catalog of work is this one. I think it’s the most food and family-like of all his art. In my interpretation of it, I can see his whole entire world. His whole lineage in mixed media. There are blue fish in the sea at the bottom right. A mountainous landscape in the middle. There’s red for blood, life, wine and energy. I see flowers, woodland foraging, and garden soil. In my mind, that blob of brown represents all the possibilities that might grow from a simple swatch of ground. And the tree. The beautiful, exuberant tree surrounded by dots of confetti-like splatters and stars. That’s the Giobbi tree. The one that represents the vitality of nature, the sparkle of life, of wife, of children all rolled up in one. I could be reading too much into it. Maybe it’s just what the title says - Fall Still Life. Maybe it’s an autumn landscape in Canzano, Italy. Or a pairing of items Edward arranged in his home studio in Katonah, New York. Maybe it represents a lot more or even possibly a lot less. Or maybe… just maybe… it’s the word, the work, that Edward’s been striving for all along.. honesty.

Cheers to Edward for sharing his family’s Italian heritage with us here in America via books, art and storytelling. Cheers to his kids, Cham, Lisa and Gena for their fantastic illustrations. And finally, cheers to the unnamed woman in Canzano, who passed this recipe along. I wish we knew your name so we could credit you properly for the delicious dish.

If you’d like to catch up with the recipe tour from the very beginning days in 2020, start here or click on any of the country links mentioned above to visit those specific posts.

Next up on the International Vintage Recipe Tour, it’s a trip to Jamaica via the kitchen. Hope you’ll join us!