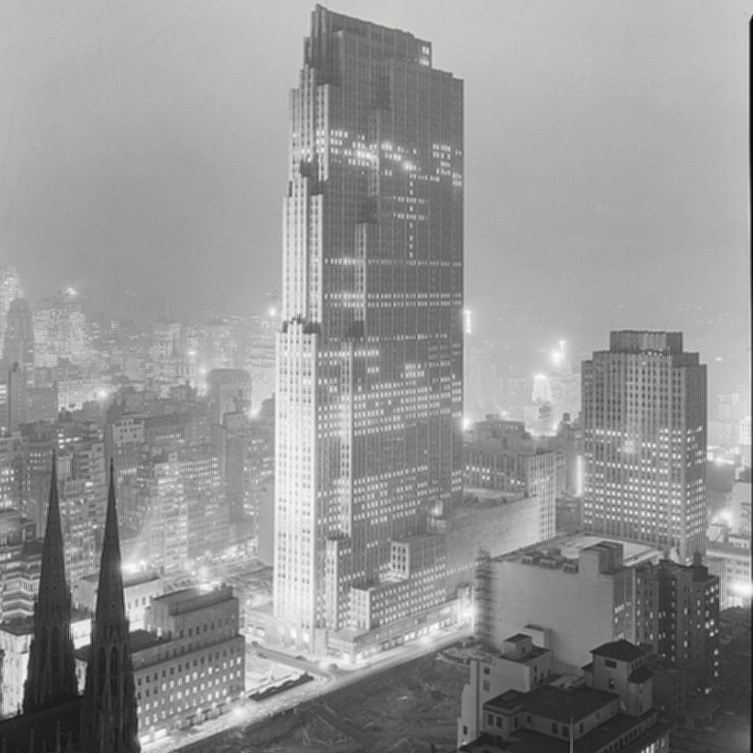

When Samuel Gottscho began his professional photography career at the age of 50, it was a leap of faith and a vast change from the garment industry salesman job he had known all his adult life. By this point, as he entered into his fifth decade, he was a husband and a father with a young daughter to raise and a long-time reputation in the industry that provided a steady paycheck and reliable consistency. But after twenty-five years of a job that both he and his father did before him, Samuel’s heart was no longer wrapped up in the lace and the fabric and the embroidery that he peddled around the city. Instead, it was his camera – his weekend hobby since the age of 20, his faithful muse, his constant companion – that began nudging him to move in another direction away from the professional life he had always known.

The year Samuel turned 50, it was 1925. New York was thriving. Museums were opening. New buildings and storefronts were being constructed. Model T’s were zipping around the city just like Babe Ruth was zipping around the bases.

In the 1920s. the average life expectancy for American men hovered between 53-60 years old. Realizing Samuel was just a few years away from possibly the end of his life, he questioned how he wanted to finish things up… by lugging around a fabric sample case or by adventuring out in the world with his camera? There was a lot to weigh between practicality and passion. Between case and camera. Between settling and jumping.

Ultimately, Samuel had the support of his encouraging wife, Rosalind, and an optimistic attitude. That, as it turns out, was all he needed.

Starting in New York City among the skyscrapers and the night lights, it didn’t take long for people to notice that Samuel had talent. His photographs captured the epitome of 1930s architectural elegance and that beguiling sense of power and opportunity that New York City stood for. Every day a story unfolded in the dramas of the big city skyline. Samuel captured them one by one in the morning mist rolling in off the East River and in the twinkling lights that turned the city into a glowing lacework of lanterns…

Exterior photoshoots commissioned by local architects led to interior photoshoots commissioned by designers, builders, and business owners…

Those led to house and garden portraits for landscape designers and homeowners…

and then to wildflower portraits pursued at first for his own interests…

but then later for clients, book publishers, and magazine editors.

At first, Samuel’s introduction to the wildflowers were daily hikes around the upstate New York hotel where he and his wife and daughter summered every year in the Adirondacks. When the gas rations were in effect in the 1940s, it wasn’t feasible to explore the countryside with the car and driver Samuel previously employed in the city. Foot travel replaced the car, his young daughter, Doris replaced the driver and the two would tottle off together to explore the woods any chance they got.

Noting the curious array of flowers that dotted the roadsides and the woodlands and how they all fit together into the broader landscape made Samuel appreciate the composition of each and every flower in a new, more visual, more vital way. As he learned, Queen Anne’s Lace or feathery petaled Bergamot or the large craggy, canopied trees found in these upstate New York hideaways were just as stately, just as visually spectacular, just as unique, as the Chrysler Building towering above Manhattan.

Enchanted with the light, the subject matter, the shape and the composition of the flower fields, Samuel found them to be little cities in their own way. Tall, short, fluffy, sparse. Each one added pops of color, variety, and form to the overall canvas that was the natural wilderness. Eventually, Samuel’s Adirondack wildflower summers were replaced with Sound-side summers spent on Long Island, New York’s North Fork.

Known as its own agricultural wonderland bordered on one side by the Long Island Sound and the other side by the Atlantic Ocean, this island surrounded by lighthouses and studded with sailboats was first inhabited by the Corchaug, Algonquin and Montauk tribes. Boasting its own never-ending supply of native wildflowers, it delighted the eye with all sorts of natural splendors highlighted by backdrops of the water, beaches, pine groves, pasturelands and marshes. Samuel photographed every bit of it.

No stranger to wild things and naturally picturesque vistas, the North Fork was home to New York State’s first farms and first English and European families. Dating all the way back to the 17th century, Southold, the town where Samuel spent his Sound-side summers was settled in 1640 by farmers, tradespeople and clergymen from England and Europe by way of Connecticut.

A fishing and farming community long before the Island ever became a residential extension of New York City, this stretch of Long Island from the tip of Orient Point to the mid-section of the island never lost its agricultural roots. Full of sprawling vineyards, seaside homes, stretches of pebble-studded beaches, open meadows and working farms that produce every sort of market delight you could ever want, it’s a food lover’s paradise from flowers to honey to wine to grass-fed beef.

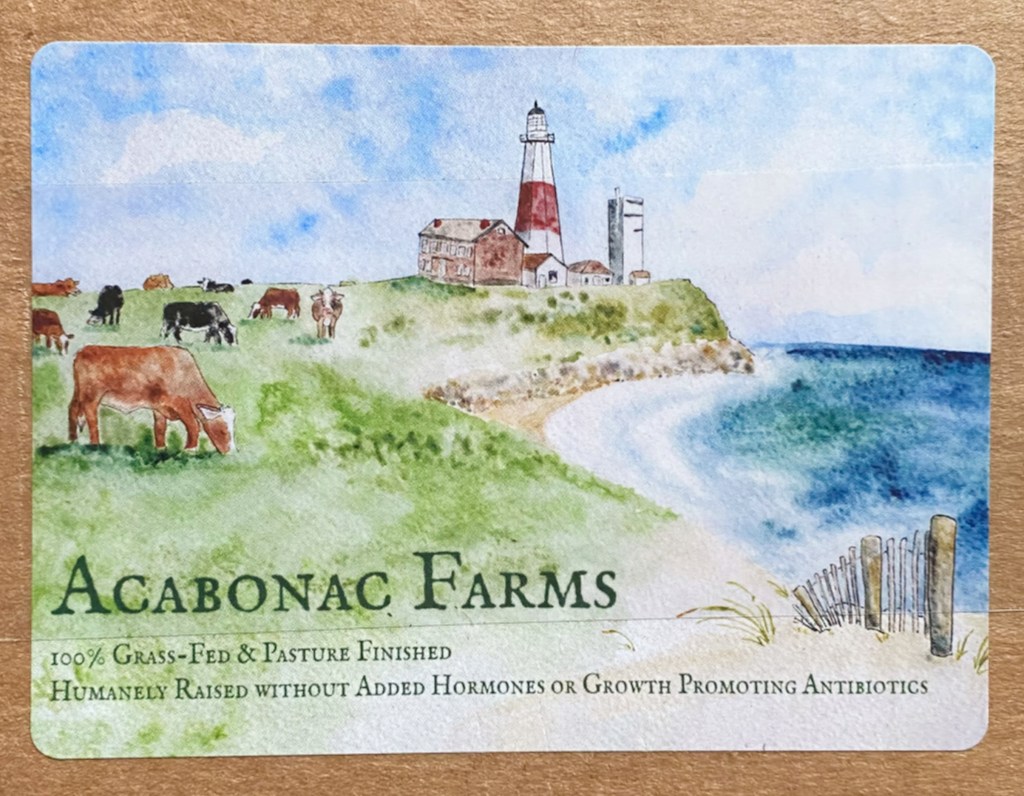

Celebrating this area’s centuries-old agricultural history, in today’s post, we are featuring a recipe made using grass-fed beef from cows raised and pastured on Long Island’s Acabonac Farms. Just a short drive down the coast from where Samuel summered in Southold, Acabonac Farms works in tandem with the natural landscape just like Long Island’s first settlers did back in the 1600s.

By embracing the unique nutrient-dense soil that makes it one of the best terrains in the state, combined with the salty sea air, the continuously circulating breezes blowing in off the water, and the well-draining composition of the soil, it’s a trifecta of a location historically known for growing good grass which in turn grows good grass-fed cows.

Throughout his second career, Samuel’s photographs appeared in publications all over the country, but none may have been more proud of Samuel’s work than his hometown newspaper, The New York Times, where he was regularly featured. In keeping that joyful relationship intact, our featured recipe for this post comes from the 1961 New York Times Cookbook and combines Acabonac Farms grass-fed sirloin steak with an unusual 24-hour marinade to create picnic-toting steak sandwiches fit to fuel any wildflower photographer’s wanderings.

Named after the patron saint of hunting, this recipe called Steak St. Hubert, can be made with venison or beef using round or sirloin cuts depending on your preference. Originally, it was meant to be enjoyed as a single cut of meat – a steak dinner complete with a red current jelly reduction sauce – but I decided to turn the steak into sandwiches so we could pack it along with potato salad and refrigerator pickles for a summer picnic getaway to see the land that so inspired Samuel.

Consisting of a unique menagerie of ingredients, this marinade contains no cane sugar and no salt but does include carrots, wine, and apple cider vinegar, which I found to be a pretty intriguing mix. A bit like Annie’s Wine Baked Brisket and Santiago Pork Roast, this is a two-day, three-part recipe to prepare but well worth the time.

Although this is a local post featuring Long Island, Acabonac Farms beef is available to any home cook no matter where you live. If you haven’t had the experience of ordering meat via mail before, the process couldn’t be easier. You simply place your order online and it shows up at your door two days later in a box packed with dry ice and the individually frozen, vacuum-packed cuts you requested.

Beef that arrives by mail can be thawed in the fridge overnight (in its original packaging) or stored in the freezer for use at a later date. For this recipe, the three packages of steaks we ordered went into the fridge for 12 hours before they were added (completely thawed) to the marinade and then returned to the fridge for another 24 hours.

The marinade is easy to put together. The original 1961 recipe called for a big bowl as the marinade vessel but I found that a two-gallon Ziploc bag worked just as great and made it easier to store in the fridge. Other than that note, the marinade recipe comes together just like this…

Steak St. Hubert Sandwiches (serves 10-12)

For the marinade:

3 16 oz .sirloin steaks cut 1/2-3/4″ inch thick

2 shallots, chopped

2 carrots, sliced

2 onions, sliced

1 clove garlic, chopped

2 sprigs of fresh thyme

2 bay leaves

1/3 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 small pinch of ground cloves

2 cups dry white wine

3/4 cup apple cider vinegar + 1/4 cup water, mixed together

1/2 cup olive oil

For the pan:

Salt

Pepper

6 tablespoons butter

For the sandwiches:

Portuguese rolls (or any soft and pillowy sandwich roll that has a crusty exterior and an airy interior)

lettuce

red onion, sliced in thin rings

Condiments (cherry jam, horseradish, mayonnaise, dijon mustard or any others you might prefer)

In a large bowl, mix all the ingredients together minus the steaks. Add the steaks and toss the mixture again.

Remove the steaks to a large (2-gallon size) Ziploc bag. Pour the marinade mixture from the bowl into the bag, covering the steaks completely. Seal the bag and store it in the fridge for 24 hours.

After 24 hours have passed, remove the steaks from the marinade bag to a large plate or casserole dish and let them warm up to room temperature while you prepare your cooking pan (about 15-20 minutes.

Salt and pepper both sides of each steak. In a large cast iron or heavy-bottomed pan, working individually, melt two tablespoons of butter over medium-high heat, cooking each steak one at a time for 7-10 minutes per side to achieve a medium rare center. Repeat with the following two steaks.

Transfer each steak as it comes off the heat to a parchment-lined piece of foil. Wrap each steak in the foil and let them rest until completely cool (about 30-45 minutes).

If you are planning to take these sandwiches on the road, the whole steaks can be refrigerated before slicing for up to 12 hours once cooled. When you are ready to prepare your sandwiches, slice each steak into thin ribbons.

Tuck the thin slices of beef between two slices of bread and call it divine or you could adventure even further and stretch your palate to include a train of condiment flavor pairings. Mustard, horseradish, mayonnaise. Maple syrup, cherry jam or hot sauce. Top the beef with a layer of blue cheese or fresh pineapple or a ring of red onions and you have a custom sandwich built just for you. Originally, the recipe called for a red current reduction sauce (an element that might not travel well), so I toted along a jar of French cherry jam in addition to the other above-mentioned condiments. A dollop of jam on top of the steak and between the layers of onion and lettuce was a magical combination of the sweet, savory kind that I would highly recommend.

A complete delight of a recipe from start to finish, the sirloin was full of flavor but not in a way that you could easily detect by the marinade ingredients alone. Most steak marinades I’ve ever tried in the past make the meat taste like the ingredients it was marinated in. Teriyaki steak for example tastes like soy sauce. A honey mustard marinade makes everything taste like honey and mustard. But this marinade was different. There was not one ingredient that overpowered the other. Instead, it combined a symphony of subtleties that left room to taste the flavor of the grass-fed beef. It made such a tender, succulent sandwich, it can best be described as pure, at every step, and every bite. Perhaps that is the magic of the salt, sea and sun of Acabonac Farms’ location. A delicious alternative to burgers and a great travel food for tailgate parties, fall leaf-peeping adventures and family football games, St Hubert steak sandwiches offer the best of New York’s local food that also happens to be accessible to everyone around the country no matter where you live.

As for Samuel and his Long Island escapades among the wildflowers, he had no worry about that average life expectancy marker in the 1920s. Samuel may have been fifty years old when he left his salesman job and professionally embarked on his new career, but it kept him engaged and enthralled for the next forty-five years of his life. When Samuel passed away in January 1971, he was 95 years old. Up until a week before his death, he was out in the field capturing the wild winter landscape, fulfilling client commissions, and working on his own personal archive that exceeded 40,000 images. What was Samuel’s secret to such a fulfilling life?

“It’s never losing the inquiring and enthusiastic spirit of the amateur,” he once told a reporter.

By the time, Samuel passed away, he was the recipient of numerous distinguished awards and accolades in the fields of architecture, horticulture, and landscape design. He was published in architectural digests, home design magazines, photography manuals, and newspapers around the country. Occasionally he would give a lecture or a presentation to a garden club or a photography circle. He was an expert for sure but he never had the bravado of one. Those accomplishments were nice, but that’s not what drove Samuel. His heart fired up at the sight of light, of composition, of shape. His heart fired up at photography and anything leading to it.

Just like the accessibility to Acabonac Farm’s grass-fed beef, you don’t have to live in the vicinity of New York City or Long Island to view more of Samuel’s work. Upon his death, he donated his entire photographic collection to the Museum of the City of New York and the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. Over 2/3rds of his collection has also been digitally archived at the Library of Congress. More of Samuel’s work has been published in a gorgeous 2005 coffee-table book, The Mythic City, focusing on his New York architecture portraits spanning the 1920s-1940s. And last but not least, there are his wildflower photos published in the petite 1951 Pocket Guide to the Wildflowers, which is how I came to be introduced to Samuel’s life and work.

Just like the camera was Samuel’s gateway to an entirely new life, Samuel’s life became my gateway to an entirely new area of the world and an entirely new vintage recipe. I’m so happy to share his story with you here on the blog in hopes that it inspires something new in you too.

Cheers to Samuel for not letting age be a factor in following his passion and for the incredible volume of work that he left for everyone to enjoy. Cheers to Acabonac Farms for sponsoring this post and for contributing the delicious grass-fed beef for this recipe. And finally cheers to the farmers of Long Island who work day in and day out to keep the agricultural history of the region alive and thriving.